Guardiola on Ice: a Symphony Blends with Heavy Metal for Brandon Naurato’s Michigan

On the core idea, language, and people behind Naurato’s quest to bring Cruyff and Guardiola’s Total Football to Yost Ice Arena

The Harvard men’s hockey team arrived at Yost Ice Arena on Friday, November 25th undefeated. The Crimson boasted a roster stacked with projectable NHL talent and the progeny of NHL alumni. The team probably had more in common with their hosts for the weekend than there were differences, but over the first twenty minutes of play, Harvard raced out to a 3-1 lead, playing quicksilver counterattacking hockey, burning Michigan in transition, and prompting play-by-play man Al Randall to wonder aloud whether the Crimson were the best team in the country.

Over the next forty minutes, though, the Wolverines clawed back into the game to eventually secure a 4-4 tie, before riding the momentum they generated through the comeback to a 4-1 win the following evening.

So how did Michigan get back into Friday’s game and provide the Crimson with the first two blemishes to their record of the season? It wasn’t with overwhelming speed and skill, but instead through steady possession play and the gradual building up of pressure that inevitably became too much for Harvard to bear.

It was Adam Fantilli cutting back at the hash marks and looking to create. It was Seamus Casey and Ethan Edwards directing traffic from the point, sauntering around defenders and switching the play to keep play fixed in the Crimson zone. It was Harvard launching the puck down for icing, desperate for even a temporary reprieve. It was Brandon Naurato hockey, and its basic principle is simple: When the defense is unstructured, attack, and when the defense is structured, possess.

In a match-up of two fabulously skilled teams, Michigan seized control through its ability to claim a territorial advantage and create chaos in the Harvard end of the rink once they got there.

After pulling within a goal late in the second, Michigan appeared in deeper trouble than ever when it conceded at the onset of the third period of that Friday match-up with Harvard. In response, T.J. Hughes won the ensuing face-off cleanly, pulling it deep into Michigan’s own end.

Johnny Druskinis retrieved the puck, before sending it to his defense partner Luca Fanatilli. Fantilli zipped it up for Philippe Lapointe, who sprung a streaking Nolan Moyle. Moyle shot the puck into the offensive zone, before winning a race to retrieve it below the Crimson goal line. Moyle sent it along for Hughes, who played an artful banked pass along the boards to Druskinis. Druskinis fired it to the goalmouth, where Moyle tapped it in.

Before Harvard could touch the puck, Michigan had won a draw, built possession steadily from its own end, traversed the offensive zone, then scored. Ten minutes later, Lapointe would tie the game, again on a goal built out from the back and scored as the culmination of an extended stay in the Crimson end of the rink.

When Mark Estapa scored to get the Wolverines off and running the next night, it was another goal born of steady Michigan buildup to work up the ice, before getting comfortable for an exploratory cycle play, the Crimson powerless to intervene.

Last Wednesday morning, in his office at Yost, Naurato sits down with the fortunate author of this unfortunate hockey newsletter to unpack the philosophy that steers his team.

He uses an Expo marker to illustrate on the whiteboard built into his desk, drawing out each concept or hypothetical as he explains it:

“It’s percentages more than anything, but this is my version of Pep Guardiola—you build it from the back, if we’re connected and we’re tight and we have options in tight, but then options wide—I’m not a soccer guy, but it’d be like punting into the sideline: We’re not just going to try and carry it out the whole time. We have to kick it wide. When you kick it wide, everything shifts to then kick it back, so that you can keep going through the middle.”

He continues: “we want to be in this area [pointing to the lane between the face-off dots up and down the rink] the whole time. Okay, but the game is played in this area [gesturing to the space outside the dots] because everyone stands in this area [pointing back to middle ice].”

This dynamic creates a basic problem: How do you break down a defense that knows protecting the inner-slot will deprive an opponent of any serious offensive joy?

Naurato invokes Guardiola to answer this question, and in doing so, he alludes to a philosophical soccer tradition that borders on the religious, stretching back to the Catalan’s mentor and exerting a fundamental influence over the form and kind of the modern game.

Guardiola rose to fame as the manager of F.C. Barcelona, winning La Liga thrice and the Champions League twice in four seasons. In three years at the helm of Bayern Munich, he won the German Bundesliga each season. Now at Manchester City, Guardiola has won the English Premier League four times.

The most successful club manager in the history of his sport, Guardiola can trace his success as a coach and his vision of what the game should be to his playing days at Barça, under the leadership of the mercurial, dogmatic, and iconoclastic Johan Cruyff.

Cruyff, as a player, was a unicorn if ever there were one. He would’ve smoked on the pitch if he’d been allowed to. He claimed that the only reason a player would need to sprint during a game was because they were out of position. He would bark tactical instructions to (or, perhaps more accurately, at) teammates while he had the ball.

His eccentricities aside, the Dutch master also won three Ballons D’Or and three European Cups (the predecessor to the Champions League). When he moved from his boyhood club Ajax to Barcelona, it was for a world record transfer fee. As a manager, Cruyff led Barça to the club’s first ever European Cup (all of his victories in the competition as a player came at Ajax).

When Cruyff guided the Catalan club to that trophy, at the base of his midfield, pulling all the strings as the side’s pivote was Guardiola. Thanks to Cruyff, Barcelona came to believe that winning alone was insufficient and that playing beautifully was essential to true success. As its More Than a Club motto suggested, Barcelona was not just a football club but a philosophical idea about how the game ought to be played. An idea that began under Cruyff’s leadership and was perfected under Guardiola.

Though the system of positional play Guardiola employs at City today is vast in its intricacies, the fundamental idea behind his process is basic and harkens back to an aphorism of Cruyff’s: “There is only one ball. If we have it, the other team can’t score.”

Where many teams might boot the ball as far as they could when faced with pressure, attempting to force play away from their defensive third and towards the attacking one, Cruyff and then Guardiola recognized that building with short, quick passes from the back could afford the sides they managed control over every match and build a structure that allowed those uniquely talented teams to express themselves.

It is this basic tenet that drew Naurato to the Catalan manager. Upon learning through tireless data collection and analysis that the majority of NHL goals begin in the defensive zone, Naurato was confused. After studying Guardiola, he recognized a basic triumph of space and numbers: “If the puck gets chipped out of our O-zone into the neutral zone, there’s ten guys right here [between the puck and the attacking goal]. If it’s down here [in our defensive end], now there’s ten guys here, there’s more space. It’s just simple logic. We’re not reinventing the wheel here.”

For an illustration of this dynamic, let’s return to Moyle’s goal:

Because T.J. Hughes wins the center-ice face-off all the way back into the Michigan zone, the Wolverines retreat and must build from the back. Harvard sends all three of its forwards below the tops of the circle, such that when Fantilli plays his breakout pass for Lapointe, the puck zips past all three Crimson forwards, leaving Lapointe and Moyle to work two-on-two against the Harvard defensemen, who must be cautious without much support from their forwards.

It means there is ample space for Moyle to shoot the puck into the zone with reasonable confidence that he will be the one to recover it (although to be fair, with Moyle, there is always a better than not chance he comes up with a retrieval even if the numbers and space aren’t in his favor).

By building out from the back, Michigan can command the space. It lures Harvard forward, only to capitalize on the pockets of ice the Crimson vacated. If instead Michigan had tried to play straight from neutral ice through Harvard, it would have been greeted with five tightly-packed Crimson skaters, affording minimal room through or around them.

So why turn to Guardiola? To adapt a formula that has earned that produced championship results across European soccer for achieving game control, sustainable offensive production, and eventually and most importantly wins in bunches.

For a team as skilled as Michigan, tactics might sometimes feel like a handbrake. Why not allow the likes of Adam Fantilli or Luke Hughes to roam as freely as they would wheeling through a game of shinny on a frozen pond? Because hockey is chaos and a shared understanding of how to navigate that chaos affords a more replicable path to its most rudimentary objectives: scoring goals, preventing the other team from doing the same, and winning games.

To better understand this process and the potential of Guardiola’s system adapted to the ice, let’s borrow a different of the coach’s paradigms. In his book Pep Confidential (which explores the process of adapting his Cruyffian system to Bayern and Germany after spending the vast majority of his playing and coaching career at Barça), Martí Perarnau explains that Guardiola “makes a clear distinction between the notions of ‘the core idea,’ ‘language,’ and ‘people.’” We will use that three-pronged approach to unpack Naurato’s version of Cruyff and Guardiola’s total football.

The Core Idea: Dominating through Possession

“The core idea” refers to “the essence of a team and its coach” and can be reduced to a variation of the aforementioned saying of Cruyff’s: “the idea is to dominate the ball.”

When asked whether it would be fair to say his team shares this ethos, albeit with a ball swapped out for a puck, Naurato affirms “100%.”

Of course, the transition from an expansive soccer field, populated by eleven players on each side, to a compact sheet of ice, flanked by walls rather than chalk lines means things won’t look identical.

“In soccer, there’s no boards, right? So it’s all possession,” explains Naurato. “In soccer, you can just bring it back, bring it back, and it seems slow. That’s kind of how roller hockey is. I think it’s great development for kids because in roller hockey, if you’re on a two-on-two, they won’t attack because possession is so massive. There’s no offsides, so if I’m on a two-on-two with you, and I don’t like it, I just bring it back, and what you’re waiting for is one guy to get too anxious, and he comes and chases you, and you beat him. Now it’s a four-on-three, so it’s all about numbers.”

As Naurato noted above, the pace of a hockey game means that you cannot carry the puck as often or as easily as you might the ball in soccer. What does translate though is the understanding that possession provides security and effective puck/ball movement within that possession is vital for manipulating a defense.

In Pep Confidential, Perarnau quotes Guardiola as saying “it’s not possession or one-touch passing that matters, but the intention behind it. The percentage of possession a team has or the number of passes that the group or an individual makes is irrelevant in itself…Having the ball is important…in order to maintain your shape, whilst at the same time upsetting the opponent’s organization. How do you disorganize them? With fast, tight, focused passing.”

This dynamic mirrors Naurato’s initial explanation: that possession play is a means of luring out a fixed and comfortable defense, anchored around the net where goalscoring must eventually happen. In his words, “When you kick it out, and they leave [the slot], that’s when plays can happen back into those spaces.” In this model, possession and scoring happen in different areas of the rink, with puck control around the perimeter baiting an opponent out of high danger areas. That movement allows Naurato’s team back to the slot, where goals can be found.

As Guardiola pointed out, even if possession can provide security on the grounds that only the team with the ball can score, it is still just a path to a bigger objective: sowing disorganization in an opposing defense to open up those quality scoring opportunities. Naurato expresses an almost identical sentiment:

“I don’t want possession just to have possession. Field position is massive, meaning possession. But we want to create chaotic possession, so it’s shot, retrieval, are they out of structure? Attack. Are they in structure? Possess. Attack, retrieve, release. Attack, get it back, then attack again, or release, meaning change sides.”

In short, the core idea for Naurato—just as for Guardiola—is to dominate possession, tilting the rink in his team’s favor and destabilizing the opposing defense to create a feeding frenzy in the offensive third.

Language: the Decision Zone, the Cemetery, and the Training

As Perarnau explains it, language refers to “the way in which the core idea is expressed on the pitch and is the culmination of a training regime which uses a range of systems, exercises, and moves to reinforce understanding and mastery of the basic concepts.”

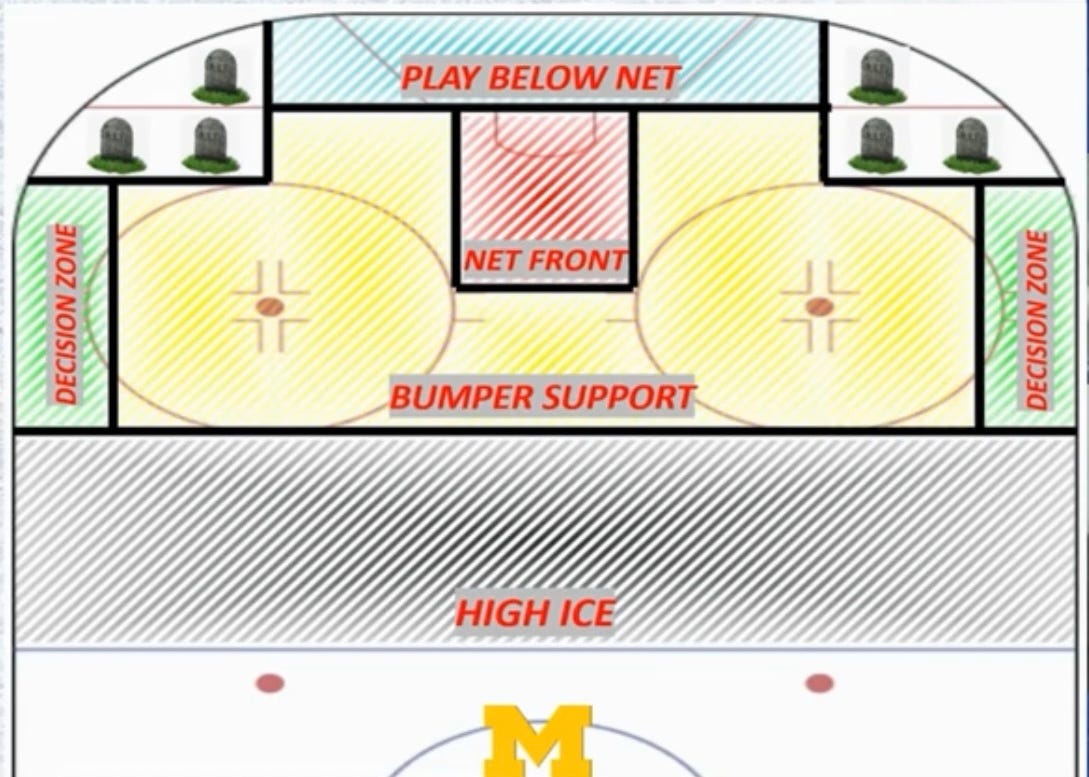

To express the language of his system, Naurato uses another trick of Pep’s: subdividing the playing surface to offer a clearer picture of the space his team must control.

The language of Naurato’s system for creativity in the offensive zone hinges on the distinction between “the decision zone” and “the cemetery.” The former, the space along the half-wall running the length of the face-off circle and extending out a few feet from the boards is the Wolverines’ touchstone for creation; the latter, as its name implies, is where that creativity goes to die.

Before getting into detail on the comparative value of those two spaces, let’s take a moment to consider how this understanding of the offensive zone came to be.

Cruyff’s vision of space was an aesthetic one; as Kuper puts it, “It turned out that beauty in football wasn’t just a by-product, but a way to win even when you lost. The beauty that Cruyff cared about was collective: football as choreography, rather than individual tricks on the ball. He wasn’t by nature a ‘one for all and all for one’ kind of guy…He just believed that the fullest expression of football was team play.”

In contrast, Naurato’s is born of voracious study of video and data, rather than Cruyffian aesthetics. This is not to say that the interim head coach does not appreciate the potential of this style to produce beauty, but rather that he is a secular acolyte to the Barcelona church.

After studying the origins of years’ worth of NHL goals, Naurato recognized that goal scoring happens in the space shaded red above, what he calls the “scoring square.” Defenses also recognize this. Thus, Naurato’s project has been identifying the optimal passages of play to unlock fixed defenses and gain access to the inner slot.

At Michigan, Naurato is in the process of developing an app he pioneered during his time with the Red Wings. It is built around shot data but also factors other variables like pre-shot movement, opposing structure. It would allow the coach to, as an example, pull up data and video for all of Moyle’s even-strength chances off the rush in an instant. He can sort by opponent, situation, or opposing structure. He can view the chances Moyle generated himself, the ones he was involved in, or the ones he was on the ice for or against. Naurato refers to it as “my brain in a platform” and adds that it expedites the process of studying film dramatically.

Through years of exploring similar data, Naurato pioneered the notion of “the decision zone,” which he prefers as a home base for offensive zone creativity because of the way it opens up options. From the decision zone, a puck carrier can make plays to the net, plays below the goal line, or plays to high ice. Recognizing that goals will seldom be scored from outside the slot, Naurato also instructs his players to be shooters within the dots and playmakers outside them.

Consider this Rutger McGroarty entry:

McGroarty gains the zone with speed, but he is confronted by four Crimson defenders in sound structure. This structure is the freshman forward’s cue to possess rather than attack, so he cuts back just above the decision zone and feeds Seamus Casey. In so doing, he turns an adverse situation (being outnumbered in the offensive zone off the rush) into a quality Casey chance from the inner slot. By not forcing play to the net or the corner where he would almost certainly be overwhelmed by Harvard defenders, and instead playing to remain in control, McGroarty creates a high-grade scoring chance.

In this regard, the decision zone exists in stark contrast to the cemetery. While the decision zone invites options for destabilizing an opposition defense, the cemetery makes a defense’s job easy. Playing in the cemetery makes it simple for a defense to contain the play, collapse, and win back the puck. By its nature, any defensive zone structure will seek to confine the opposing attack to a single corner; by playing into or from the cemetery, an attack does that work of containment for the defense. As such, Naurato has a strict rule: Never support the puck in the cemetery.

McGroarty’s set up for Casey also illustrates the principle with which we began: attack an unstructured defense and possess against a structured one. Maintaining possession involves creating a numerical advantage in high ice (the portion of the offensive zone above the tops of the circles), aimed to draw out defenders only to set up a convergence at the net via the space those defenders vacate.

Crucially, possession play needs to involve switching sides, which is the best way to coax an opposing defense out of its structure. This can be done through the simple rim release: playing the puck around the boards to an empty pocket of space on the opposite side of the zone and forcing the opponent to pursue it.

In Naurato’s words, “[With the defense set in its structure, the scoring square] is cluttered up, [so] I would want to release it out to then pull people away and then as they come away other people are moving into these areas, and we’re delivering pucks, and you have have a chance.”

Naurato stresses that the old-school cycle (which would often begin and end in the cemetery and wouldn’t switch sides) is insufficient; it can be defended without forcing the opposition to move out of its structure. By switching sides through a rim release, Michigan forces its opponent to, at the very least, reset its structure. Another advantage of the rim release is that an opposing defense can never set up to take it away, because doing so would leave the slot wide open from the jump.

In addition to creating offensive opportunities, playing for possession rather than forcing an attack against a structured defense offers a layer of defensive security as well.

Here, Naurato provides a hypothetical: “Say we had three guys involved [at the net], and we were trying to pass out to our defenseman [at the point]. Well, if the puck gets turned over, you’re in big trouble…If we’re attacking with three guys in high ice, and this player shoots a puck, we now have people in all those areas to get the puck back.” In other words, losing possession if you have numerical superiority in high ice leaves you much less vulnerable to a counterattack than giving the puck away with just a defenseman or maybe two standing in the way. As such, playing for possession in attack reinforces defensive solidity.

To implement this system requires a delicate balance of training players’ technical skills and positional awareness. Just last Tuesday, the Wolverines opened practice working on a skill Naurato refers to as a “shave ice delay,” essentially a move to pull up and survey options upon gaining the offensive zone, with the resulting spray of ice lending the term its name.

The team is divided into groups of three or four, each beginning at a face-off dot and facing the boards. One by one, players cut back and forth several times, honing the habits and fundamentals that will enable them to exploit the space they create through Naurato’s system. At one point, a jocular Casey pulls his hand from his glove, flashing different numbers of fingers to ensure Brendan Miles has his head up as he completes his turn. Without the Children providing a din, the sound of skates carving ice reverberates through Yost. Before practice can move on to the next drill, director of hockey operations Topher Scott rounds the boards with a shovel to rid the rink of the excess snow kicked up by the exercise.

In this sort of technical training, Naurato emphasizes habits; details like head placement or the progression of the body through a turn are more than significant enough to attract his attention.

Naurato also prioritizes “transferability” in drill design, considering it essential to hone these skills in an environment that will mirror game situations. This means shooting off passes, rather than carrying the puck to a desired area. It means acquiring pucks through realistic means to open a drill or putting bodies in realistic spots to simulate the reads and options that players will see in a game.

We’ve written before about the Wolverines’ use of different iterations of a Cruyffian staple: the rondo, a drill that trains players in the crisp decision making and understanding of space demanded of players in a possession-based system.

To Naurato, the idea of transferability is simple: “Why would we work on neutral zone transition and then end that drill with a controlled entry, when you should end that drill with a chip to space, because you’re going to feed your forecheck, because they have players above and we’re trying to get in?”’

In reference to one drill that followed last week’s ice shaving, which asked defensemen at both ends of the rink to exchange a pass then make a breakout pass before being joined to work the cycle from the forwards who received pucks from the opposite pair, Naurato says “We could do that drill ten different ways. Minnesota runs a one-two-two, so those are the options against a one-two-two. If we play Wisconsin, who does a two-one-two in the neutral zone, those options would change. So you have core formatting drills or foundational drills and then you can always tweak them with different progressions based on what we need to be better at or what we might see.”

In the end, all of these drills and details are a means of familiarizing players with the language through which the core idea is expressed, to borrow again Perarnau’s phrase.

The People: Heavy Metal, Symphonies, and Diversity of Style

When it comes to “people,” the third pillar of Guardiola’s tripartite structure, the system’s adaptation from the pitch to the rink means that beautiful possession play needs to be supplemented by something different.

Perarnau notes that the complex Guardiola system depends on having players willing to learn its principles. Here, Naurato’s acumen as a teacher is essential, but, in translating the system to hockey, there emerges a need for variance in personnel that Guardiola does not always require. As Naurato pointed out above, soccer’s playing surface makes it easier to remain in possession, reversing field whenever confronted by a numerical disadvantage.

As Naurato sees it, bridging the gap between the two sports requires control of the net front: “It’s not the beautiful possession. That’s what I thought six years ago. [Playing with four guys in high ice] is beautiful, but there’s no one at the net, that’s where you score.” Possession play needs to be balanced with directness and simple efficiency to find team success. To illustrate this point, he cites two of the best teams to ever take the ice in his home state: the dynastic Red Wings of the late nineties into the early aughts and the 2021-22 Michigan Wolverines.

With regard to those Red Wings teams, Naurato points out that the imperious Russian Five and their ornate passing sequences were backed up by the rugged simplicity of the Grind Line. In the case of last year’s Wolverines, he highlights the import of the team’s veteran fourth line—composed of Nolan Moyle, Jimmy Lambert, and Garrett Van Wyhe—to the team’s Frozen Four run.

It’s not that fourth liners like those three cannot play possession hockey but rather that their version of possession looks different. As Naurato points out, “Van Wyhe, Moyle, Lambert, they can release pucks, they can hunt down retrievals, they can get to the net. And then the Johnsons, the Beniers, the Brissons can play the beautiful possession game, but, if you can do both, you almost have rhythms in the game where Van Wyhe and them would be like heavy metal, where Brisson and them would be a beautiful symphony. You can change the rhythms.”

With a smile on his face, Naurato offers a different hypothetical:

“Imagine in practice, where I put on the symphony music, and it’s puck possession, switches, and high ice, and then you put on heavy metal and you dump it in and you run a guy, and then you blast it to the net.”

In this regard, the importance of people is not just their willingness as students but also the value they provide through their diverse skills. As a coach, Naurato’s task becomes putting those players in positions to maximize their abilities.

A player, even a talented one, operating in a role that doesn’t suit them is “not going to help make money…and not going to help us later…You put guys in positions to do what they do to have success, but I don’t want them to be one-trick ponies, and that’s where development comes in.”

For Naurato, this kind of diversity in style is essential to finding a way past opponents that present different challenges: “Your top two lines play a certain way, your bottom two lines play a certain way, so now you can play against anyone. Different guys will step up based on the competition.”

To conclude, let’s take a moment to consider some context. Brandon Naurato is an interim head coach, thus he is in a fundamental way auditioning for a full-time role. The editorial stance of this publication as to Naurato’s long-term fitness for the position is well known, but his interim status creates a fundamental instability that invites a roller coaster of speculation and punditry.

After the 7-2 loss to Ohio State the weekend before last, Naurato can’t possibly be up to the full-time job. After a 9-2 win over Boston University earlier in the season, it was time to print national championship t-shirts. Rather than allow oneself to be swept up in the game-by-game ebbs and flows based on Naurato’s work with an inherited roster, I would contend that evaluating his fitness for the Wolverines’ long-term job is best done by considering his process.

This year’s Wolverines could get hot at the right time and finally hang the program’s tenth national title banner after a twenty-five year wait. They could also stumble down the stretch in the Big Ten and miss the tournament entirely. This year’s team is loaded with talent, but it is young and still learning how to manage games. Evaluating Naurato based on this year’s result, whether it is one of those extremes or somewhere in between, would be short-sighted.

Michigan has not endured a twenty-five year title drought because it didn’t bring enough talent through Ann Arbor. What the Wolverines have not always had is a cohesive system for maximizing that talent.

There are no tactical silver bullets, no system so masterful that it guarantees success. Even the illustrious Guardiola has been unable to capture the Champions League since leaving Barcelona.

However, with Naurato installed, Michigan hockey has begun the project of building a system and identity that can take full advantage of the talent that has graced it for years and will continue to do so in the future. If the program would like to hang more banners in Yost’s rafters anytime soon, it would be wise to see that project out for years to come.

Thanks to @umichhockey on Twitter for this preview image. You can support our work further by subscribing or by giving us a tip for our troubles at https://ko-fi.com/gulogulohockey.